With Comi-Comi a space for longer writing, Sound-Sound tries to keep things simple and share what catches my eye, whether that be an exhibition, book, film, or music.

This edition for better or for worse is a strange one. It discusses strange forms of distance and the ways that distance has been shortened through obsolete media lovingly brought back to life. In Japan it’s Golden Week so everything is slow including me making this an even stranger proposition fighting to put an end to this estranged episode before moving on.

Morag Keil “Postcards from Edinburgh”

April 13 - May 17, 2024

galerie tenko presents

at the Shibuya Metropolitan-2 Housing complex (above the Toei Bus garage)

Higashi 2-25-36, Shibuya, Tokyo

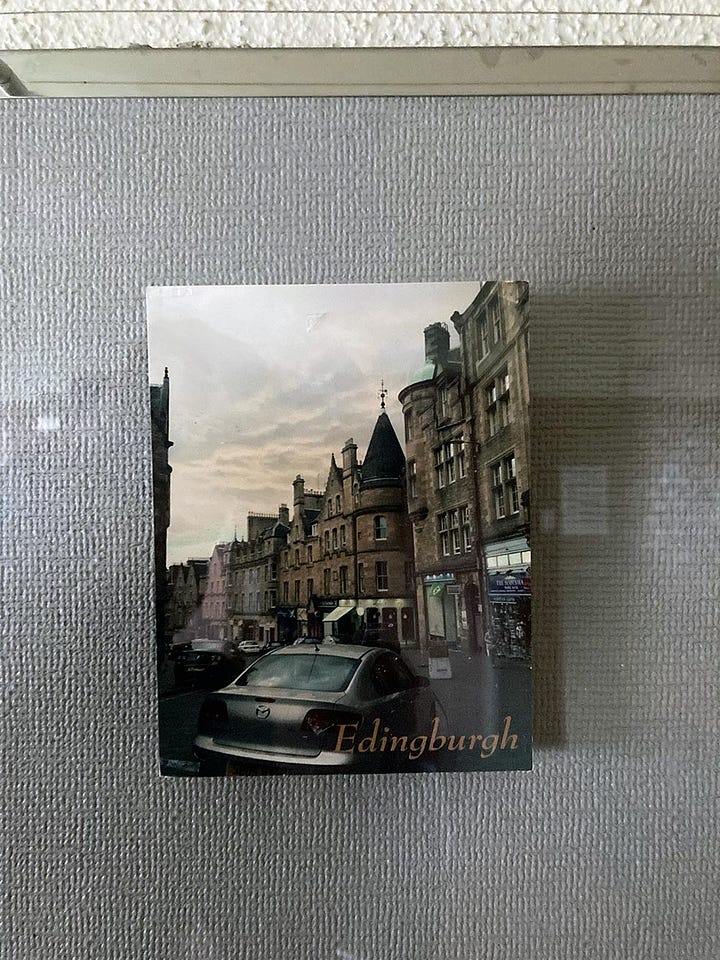

The large slender length of a housing estate, the Shibuya Higashi 2-chome 2nd Apartment complex hovers effortlessly over the Toei bus garage below. The terminus is both the first and last sop of almost every bus in the city. Meanwhile, an expedited route of distant travel takes place on the floors above. A series of small neglected signboards surrounded by a barricade of bikes picture Edin(g)burgh in a different light (and an extra letter) — each one brightening the corners of communal concrete. 1

From Berlin, the London-based Scottish artist Morag Keil sent gallerist Tenko in Tokyo 10 picture postcards of her hometown Edinburgh found on ebay. From Berlin a town they both call home a short conversation takes place alongside embroidery and decorated calendars made by other residents on other floors.

Postcards share casual details and short descriptions of each photograph, one picturing a local clock that hangs in Edinburgh and still tells the time. It’s the transience of travel, their memories of home be it in Edinburgh or Berlin, and correspondence without the baggage of actually being there describe an experience of ‘passing through’ knowing that the time on that clock bears little relation to the time of the person reading the postcard apart from it being 8 or 9 hours behind that of Japan. And with names and addresses barely legible, each tiny frame shares a rare private moment; the oddness of feeling attached to somewhere similar. It’s as if the tower block has a mind of its own winding away the hours by imagining somewhere disconnected from the real world. Postcards remain on display until the 17th. Like the dial still hanging in Edinburgh, their installation is visible around the clock.

Theaster Gates: Afro-Mingei

Mori Museum of Art, Tokyo

April 24 – September 1, 2024

So much is happening in what Gates considers his biggest show to date. It helps to forgo other ideas of folk and tradition and better to think of Gates as a custodian bringing forth the contributions of communities both locally in his hometown Chicago and further afield, namely Japan, communities overlooked or taken for granted. Afro-Mingei is a line of enquiry threading these two together — an African American community that has seen its urban fabric revivified over several decades. The other is rural Japan and Japanese traditions that were once responsible for the merchant trade of silk, soy (shoyu) and spirits (nihonshu) throughout the country.

Mingei developed in the 1920s as a philosophical approach to folk craft. Tokoname, Aichi, was and continues to be a city know for its modern production of Japanese ceramics. Elsewhere throughout Gates exhibition collaborations with fashion houses Prada and Bottega Veneta restored other styles of craft with the help of artisans to embellish the production of his own ceramic series and a good portion of “Afro-Mingei” is devoted to a archival collection of works by Tokoname potter Yoshihiro Koide, works acquired after Koide passed away in 2022. Other rooms reference the presence of black culture in printed literature and the production of American magazines like JET: The Weekly Negro News Magazine, founded in 1951 and which was known nationally for its support of a burgeoning civil rights movement.

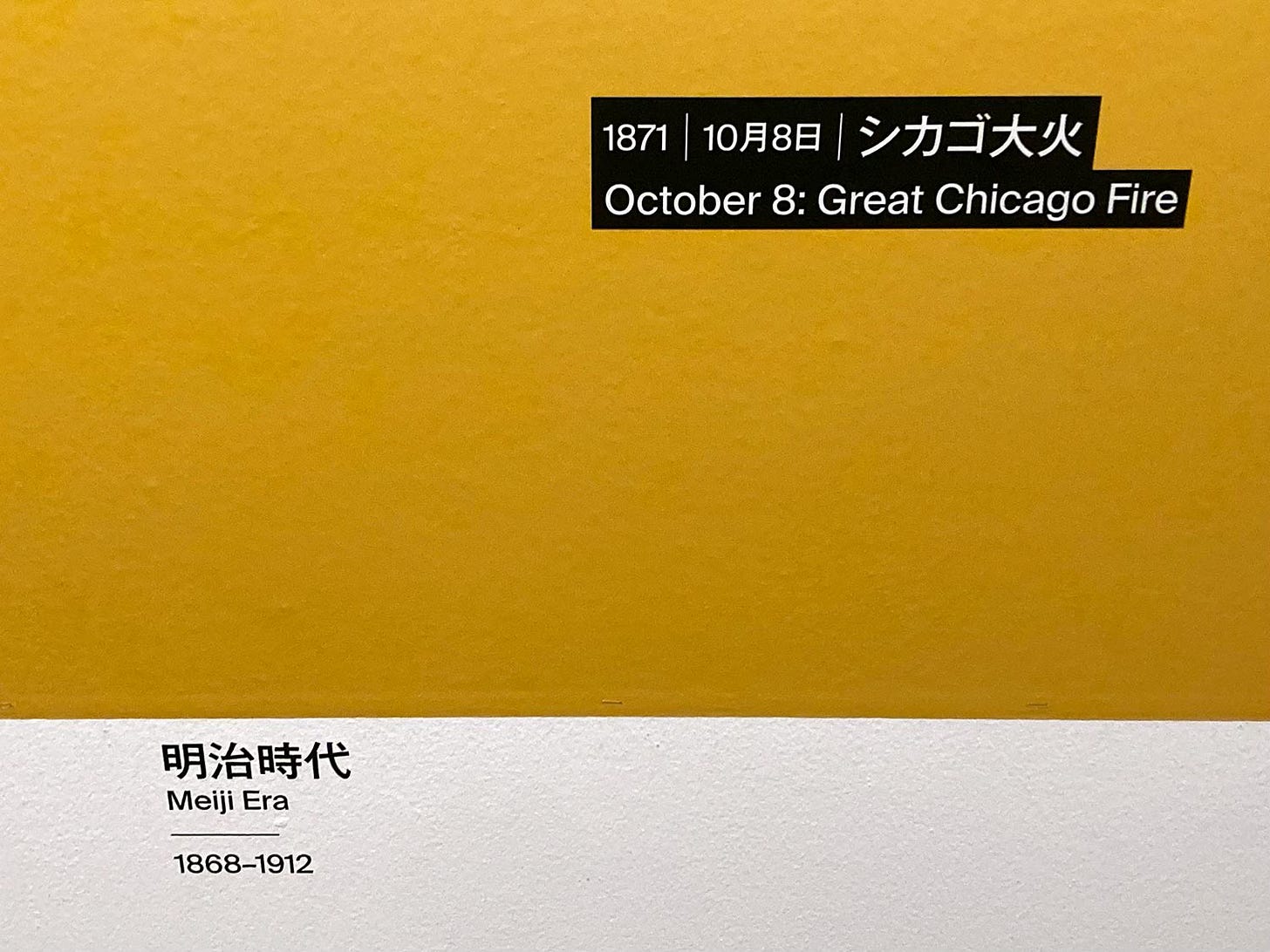

One room is the most propositional of pieces in the exhibition (and sadly one of the most under-explored. A timeline that spans from feudal period Japan and America during the slave trade runs concurrent events in Japanese and American cultural history side by side, above and below each other. At times, events appear to overlap, and inexplicably compound their effect into moment of more widespread meaning and significance. One issue of Jet magazine from 1968 sits alongside a group photo featuring Mingei advocates Hamada Shoji and Yanagi Soetsu with British artist and teacher Bernhard Leach and the Bauhaus-trained ceramicist Marguerite Wildenhain at the American private art school Black Mountain College in 1952. Barack Obama is seen being sworn into office in one timeline photograph dated January 20, 2009. Revolution in Tunisia sparks Arab Spring uprisings across the Middle East and North Africa in 2010 and the following December designer Yanagi Sori, known for merging mass-production with craft, is noted to have passed away in 2011. The coincidence of these and others events is presented as seemingly prescient while wildly divergent — the birth of modern Japan welcoming in the world with the Meiji era is recognised alongside the Great Chicago Fire several years later — reimagining history as chaotic where a butterfly effect of coincidence has given rise to shared experiences however unexpected or unlikely. It makes for a fascinating way to view a country’s history through the lens of others even when those consequences are not shared.

A Heavenly Chord (2022) with a Hammond B-3 organ and its trail of cables tied to Leslie speakers hanging from the wall reverberate as each speaker spins internally as if waiting to explode. The instrument encased in mahogany facing the salvaged floor of a local Chicago floor appeared to share the same origin. Gates and members of his gospel choir The Black Monks even performed to an onlooking crowd huddled around the organ and raked benches. Their sound combined with music from the room next door being played on a long wooden counter top emblazoned with the phrase, “Shinto Pentecostal” in what must be the most vivid expression of Afro-Mingei — a spiritual reawakening.

Ho Tzu Nyen: A for Agents

MOT Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo

April 6 – July 7, 2024

Ho Tzu Nyen is a Singaporean artist and film maker who describes film making as an idea in the making; a thought in motion threaded through research. While time flows in a straight line, “A for Agents” his exhibition of work past and present willingly jumps back and forth to ask questions of its audience.

Exhibits centre on Singapore with its mix of colonial and precolonial history. Works such as “The nameless” (2015) with the figure of Lai Teck, leader of the Malayan Communist Party from 1939 to 1947 describes the uncertainty of history. Lai Teck was Vietnamese by birth and while in office a triple agent working for the French, British and Japanese police while leading the communist party. “The Critical Dictionary of South East Asia” (2017~) uses each letter of the alphabet to ask what is South East Asia, a region not connected by language, politics or culture. The term was unknown locally and only came to be when Allied forces during the Second World War tried to liberate the region from Japanese occupation. “Voice of Void” (2021) looks at the Kyoto School of philosophers and asks what this heterogenous group of scholars with all of its ambiguities and contradictions or people like Miki Kiyoshi or Tosaka Jun, were thinking during a particularly troubled moment in Japanese history. “T for Time” (2023) is the most recent work on show. Although difficult to pin down, Tzu Nyen asks what time would look like described linearly through film and its multiplicity of memory and nostalgia.2

Indeed, time plays a pivotal role throughout the exhibition and briefest glimpse of recreated moments from Yasujiro Ozu’s Late Spring (1949), appears in the projected background of “T for Time” (2023). Coincidentally, Ozu is said to have spent time in Singapore — then known as Shonan — making a propaganda film during the Japanese occupation but it was never finished. The question of why looms large. Late Spring (1949), ends with the main character peeling an apple and as Tzu Nyen explains is echoed by the Japanese novelist Atsushi mori, a trained Topologist, used the same image to describe time as irreversible and unending.

With works borrowing from Hollywood cinema and others borrowing the language of computer graphics, history is pictured as incomplete. As onlookers, the question of our own agency remains; the answer for Tzu Nyen is an ongoing process.

Book: “Where Europe Ends” by Yoko Tawada is a book of short stories ending with as the main character headed for Moscow passing through Europe aboard the Trans Siberian Express. Tawada describes the Russian matryoshka and Japanese kokeshi doll as keeping difficult memories awake while also describing Siberia as a land of frozen sleep.

Film: All of Us Strangers (2023) directed by Andrew Haigh, was adapted from the Taichi Yamada novel Ijintachi to no natsu (1987) — the title literally translates as Summer of Strangers; the book was published in English as Strangers. 3

The new adaptation begins in London with the sky another character looming over the main character’s empty tower block amplifying their own detachment, out of reach and out of touch with the rest of the world. The tower block becomes both refuge and prison cell until he hears a knock at the door. Both film and book is a story about human connection while revisiting the past in the most vivid way possible.

The book was also made into a film shortly after the book and set in the delirium of a Tokyo summer. Like Andrew Haugh’s film, the lead character is a screen writer who begins to unravel through an encounter with his past. Known for his wonderfully delirious horror comedy House (1977) director Nobuhiko Obayashi developed The Discarnates (1988) as a horror film suffused with themes of nostalgia and lost love. Andrew Haigh’s film All of Us Strangers (2023) is more grounded but the ghosts remain. Instead they appear from the edges of a personal history that has been soundtracked by the 1980s telling a more heartfelt story.

Yoko Tawada and Taichi Yamada describe being caught in between cultures, constantly in motion and displaced by their own predicament; what another prominent director describes as “a model of utopian storytelling and utopian traveling.” The same is true of Morag Keil’s postcards. The ambiguity of Theaster Gates’ Afro-Mingei is both a way of drawing out things that have mattered to him personally as well as places that have a greater significance. While the films of Ho Tzu Nyen jump back and forth to describe the contradictions at the heart of shared history.

Miswritten, the stray typo and homonymic ‘Edinburgh’ feels and sounds more familiar, even though it almost certainly a simple typo. “Edingburgh” is how it appears on the postcard displayed on floor 2. With hindsight, I should have explained my version with (g) written in brackets a little more clearly. Considering we all experience a city differently why not the spelling as well. Edinburgh has a long history of adopting names. The Scottish Gaelic name of Dùn Èideann dates back some 2000 years. The old Gaelic name Eidyn and more recent Dunedin are others. Meanwhile, Edwinesburh, is more controversial and considered a work of pure fiction said to date back to the 12th century and David I, King of Scotland (1124-1153).

The Catholic saint and philosopher Augustine (354-430) writes, “What then is time? If no one asks me, I know; if I want to explain it to a questioner, I do not know.”