Positive entropy

Tam Ochiai, Yoko Pinkham, Masaya Chiba

According to physicist Erwin Schrödinger, negative entropy (the reverse of chaos) is a measure of life’s distance from what could be called normality. The more normal things are, the less entropy there is. The signboard above knew nothing of this. It simply spelled out what I was already thinking on my way to yet another gallery. Negative entropy – more ordered, more predictable, and never spontaneous, could best describe the order being wrought upon Ōtsuka Station as it emerged from months of construction revealing an elegant plaza and some suspicious public sculpture. If office work felt like negative entropy, wading through all of this to visit the far side of town swung boredom the other way, towards positive entropy – more chaotic, less predictable and always spontaneous. Some parts of town would never disappoint and whisper subconsciously through an itinerant screen.

“Art […] has to do with spirit, not with decoration.” 1

Chastised by the swap shops and bargain basements, signage punctuated Tam Ochiai at Tokyo’s Hermes Le Forum, making “Tacitum Lucidem” hard to fathom at times. The show also coincided with a period of peak frustration as the awkward and aloof city struggled with a poor self-image as it witnessing the role of Olympic host replaced by a slowly unfolding non-event. The signs were there already.

Ochiai lives in New York where both ‘chic’ and ‘cosmopolitan’ are as useful as they are useless sources of inspiration. Punk or new wave, European avant-garde or Dada are welcome strangers as far from present-day America as they could be, yet each of these against each other and they seem strangely vital. Everything has two places, he declares at one point, with an exchange of different things he’s found in flea markets combined to mirror the gift Meret Oppenheim and Max Ernst once exchanged as lovers. He dwells on this image of romance with the thought that pushing work out into the world with your bare hand gives birth to an idea however short the lifespan. The idea of death is never far behind and so builds an ashtray in the form of a 3-minute sculpture.

There is no doubting his distant lifestyle in the context of today is in mid-quarantine. Notes on Europe, openings, and an overseas residency are frozen solid in glass cases, tied together as random, inescapable geography. There is warmth to these notes but where do they end up apart from being behind glass? Minimal and restrained, works dupe the viewer into sidestepping stories behind each and every brush mark. Perhaps memory is a way of treating repetition and language as the real heart of the show and not the objects. Every photograph of food or carefully arranged ashtray, constellation made from shoe horns or oyster shells or even his sleeping cat laid across a piano synthesizer humming gently on the floor is a way of breaking free of institutional confines. If paintings were music they might be 10 or more minutes of noise at the push of a button, yet the cat synthesizer still took required a member of staff to push the Replay button once in a while. That self enunciating signboard in Ōtsuka now seemed less ridiculous.

Ochiai had triggered a certain type of anxiety that day. In the absence of something concrete, all of his sunny, deft, deliberate ideas felt lost as if inside-jokes. They nodding knowingly at history as his giddy eye remained privately focused. This was a language of his own whether it mattered or not. And yet one group of works gave everything away delivering the most honest character reflection — as the show’s title suggested. That Obscure Object of is based on an argument between the actress Carole Bouquet and the director Luis Buñuel as they worked on Buñuel’s final film, “That Obscure Object of Desire” (1977). Desperate to finish Buñuel replaced Bouquet midway through its production with another actress. He decided the best way to solve this crisis was to ignore it altogether and so both actresses appeared on screen in the same role without explanation, cementing Buñuel’s reputation as the father of surrealist cinema. Avoiding the pandemic, Ochiai had now dropped the word “Desire” to make his own title, noting “Like this, there is something that is fixed that is also not fixed.” Spelling out the current unpredictability with tongue firmly in cheek his eyes shift and you wonder whether Ochiai is also a surrealist.

Everyday Surrealism

Later that day Ginza streets had been replaced by row after row of shuttered Downtown shops. The old city normally came to life in warmer months but it was hard to tell if shops were closed for good or not when it was this warm, this early.

Yoko Pinkham at Lavender Opener Chair, a gallery and former florist shop in Arakawa on Nishiogu’s Kyuodai Street was showing embroidered artworks inspired by old console games, Studio Ghibli and European Arabic illuminated manuscripts 装飾写本. Drawings are planned with an iPad before hand-tufting them into rugs with a gun. Working from behind, she power-threads a needle through taut fabric which is then turned over and trimmed by hand.

I had turned up unannounced just as they were preparing for a meeting. The meeting began and the mood changed so after staring quietly at either wall I slipped outside to glimpse at work hanging in the window. It wasn’t until I overheard her point out the cast iron grating and block-work lining the street that a faint trace of Studio Ghibli or hint of Isao Takahata’s documentary The Story of the Yanagawa Canals 柳川堀割物語 began to jump out. This is where tradition and the mind both meet, where the solitary escapism of RPG and the urban landscape mix with her everyday surrealism: Details from the iron step, the brick and asphalt, the cobbled street and tanks pooled with rainwater, sprinkled with blossom and woven into almost every rug.

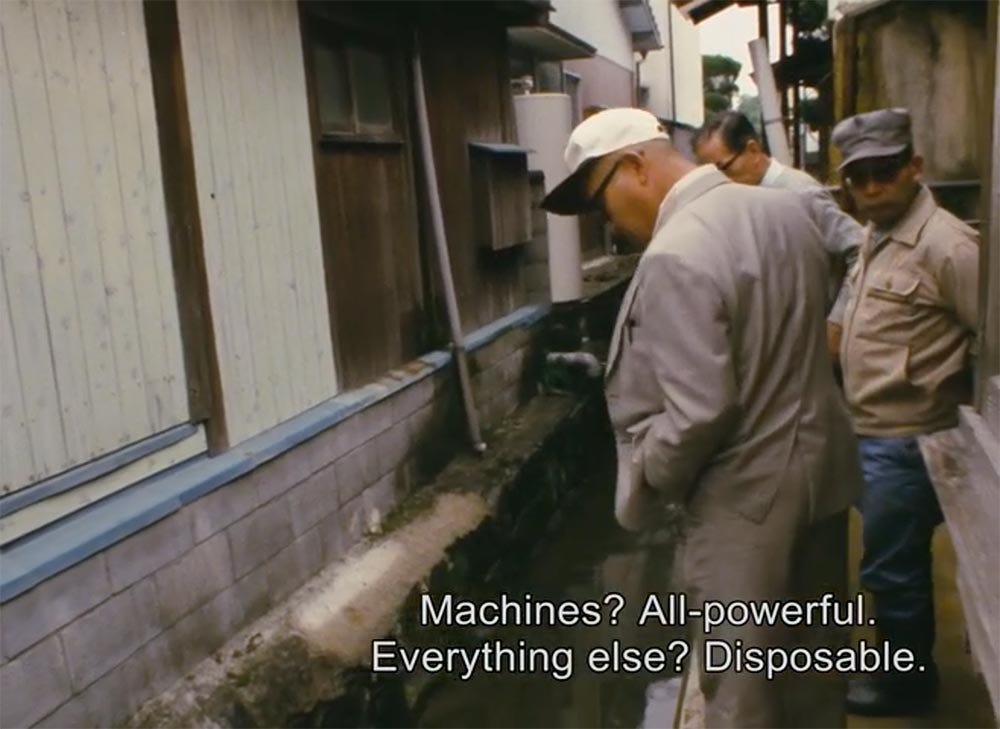

Past and present sat side by side, and I remembered seeing textiles from Mika Tajima's Negative Entropy series facing an old dagger in a local museum in Okayama. Pinkham and Tajima were allies in a way but their process was different. Tajima explicitly connects craft, technology, knowledge and wealth. Patterns are produced through the process they depict. The sound of a Jacquard loom and data storage sites were recorded, illustrated and woven with a Jacquard machine simplifying the production of complex textiles. Designs were transferred to square paper then translated to a sequence of punch cards guiding the threading process. The ongoing series draws parallels between dying crafts and burgeoning social media, between the old industrial, material economies supporting a community and the digital, immaterial economies stretched to communities everywhere.

Pinkham on the other hand is more direct, noting that sensation and touch are as important as the drawn-out making process. She wants rugs to be felt not merely looked at and supports the economy of their interaction. The escapism of the RPG console game is a world away from the street outside but is grounded by an economy linking passers by with the gallery and kitchen inside. Tohmei diner灯明 operates at night and sources produce from Yamagata. It doesn’t take long to realise how artist, gallery and diner are all something similar in the vein of FOOD, the artist-run kitchen project of Carol Goodden, Tina Girouard and Gordon Matt-Clark that opened in a old New York bodega in 1971. Cultivating a community is also the motivation behind LAX BAR by Christoph Meier, Ute Müller, Robert Schwarz and Lukas Stopczynski, an ongoing project reimagining Vienna’s famed American Bar by Adolf Loos. Each visitor becomes an actor in their walk-in sculpture and late night bar, all a part of the undiminished economy of shared experience. Otherwise known as drinking.

Even though the mood in the gallery had relaxed I walked around the block some more catching tannoy sound drift from street to street at the turn of the hour. With my phone in the air I grabbed at the sound of voices, of muffled news, announcements, and infomercials. I'm sure this recording now lives on a cloud server somewhere, along with a million other files, leveraging an economy of its own. The once audible infrastructure of machinery — shifting punch cards, shuttling looms and threading needles — and the sound signaling the start and end of each day had become tannoy announcements for an entire community, for anyone or everyone interested.

If there is something about the mode of production giving rise to independent spirit, this artist-run space was a pure example of it. Pinkham’s rugs feature the ever-present nostalgia of streets filled with more shops closed than open while picture landscapes swings from decorative manuscripts and the spirit of 8-bit processors and early consumer electronics. By now the afternoon had turned to night. COBRA dropped by for a drink before heading home and we both left as soon as guests arrived that evening. Walking to the station I caught the only tram line left in Tokyo. A short ride later and I was home. The next day I headed out once again and this whole adventure started over.

Human Zoo

The next day was warmer. There were no quiet backstreets just an overhead expressway to avoid. Masaya Chiba at Tokyo Opera City was the last place I visited that week. At the centre of the show were his two pet tortoise, Jennifer and Laura, moving through their long connecting bark-lined track. There were paintings guiding you to listen here or look there. At one point, I picked up a pair of binoculars and climbed a step ladder only to end up staring at someone sketching a painting of a sketch. Regardless of the voyeurism, I left wondering whether I was the one on display: Was I the exhibit and the animals visitor and critic combined? Every painting was angled towards them anyway. Then I remembered the model of Shinjuku Station I’d once seen in the basement of Shinjuku Station. It could have been the miniature city model Philip Seymour Hoffman once built as “a way of acting independently, in violation of instruction”. By this point reason had left the room.

Meret Oppenheim was once at a Paris café with Dora Maar and Pablo Picasso, who noticed her wearing a fur and metal bracelet. Anything could be covered with fur, he joked. “Even this cup and saucer,” Oppenheim replied. “Waiter, a little more fur!” That moment sparked what became her fur-lined teacup Object, 1936. “Object exemplifies the poet and founder of Surrealism André Breton’s argument that mundane things presented in unexpected ways had the power to challenge reason, to urge the inhibited and uninitiated (that is, the rest of society) to connect to their subconscious—whether they were ready for it or, more likely, not.” 2

Past issues:

1. Burn it Down, Build it Up

Meret Oppenheim, quoted in Lynne M. Tillman, Don’t Cry…Work: Conversations with Meret Oppenheim and Carla Liss and Lynne M. Tillman (London, 1973)