Nerves and New Skin

Mayumi Hosokura, Sung Tieu, Tokuko Ushioda

Every good story needs a hero, to “tell the other story, the untold one.” 1 Just as Meret Oppenheim had little patience for convention, turning the flash of fur on her metal bracelet into an Object that repulsed and charmed in equal measure, Virginia Woolf invented her own glossary while developing the essay Three Guineas (1938) at a time when the only thing the English language offered was ways to deflect on oncoming, inescapable threat of war. She resolved to think of words describing bacteria, among other things, as heroic; a thing that carried something else. Writer Ursula K.Le Guin recognized Woolf’s glossary and the use of the term Botulism as a type of bottle, a wordplay that carries you with it. The vessel would change with its content, adapting, growing, spreading to other things, other words, other people. The bottle was the hero.

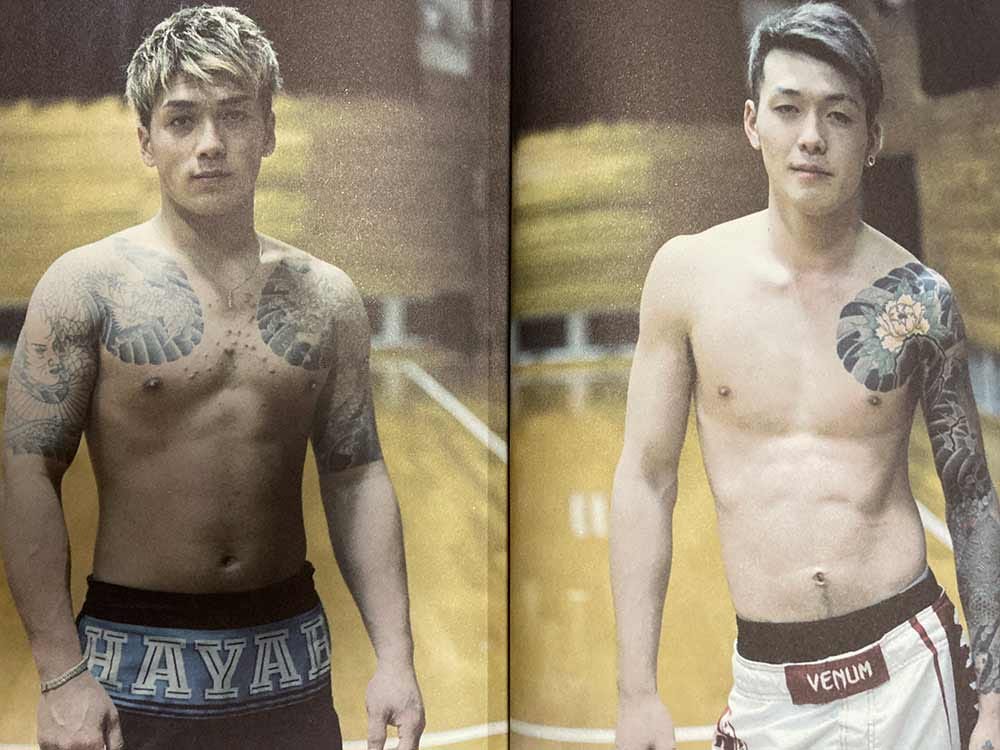

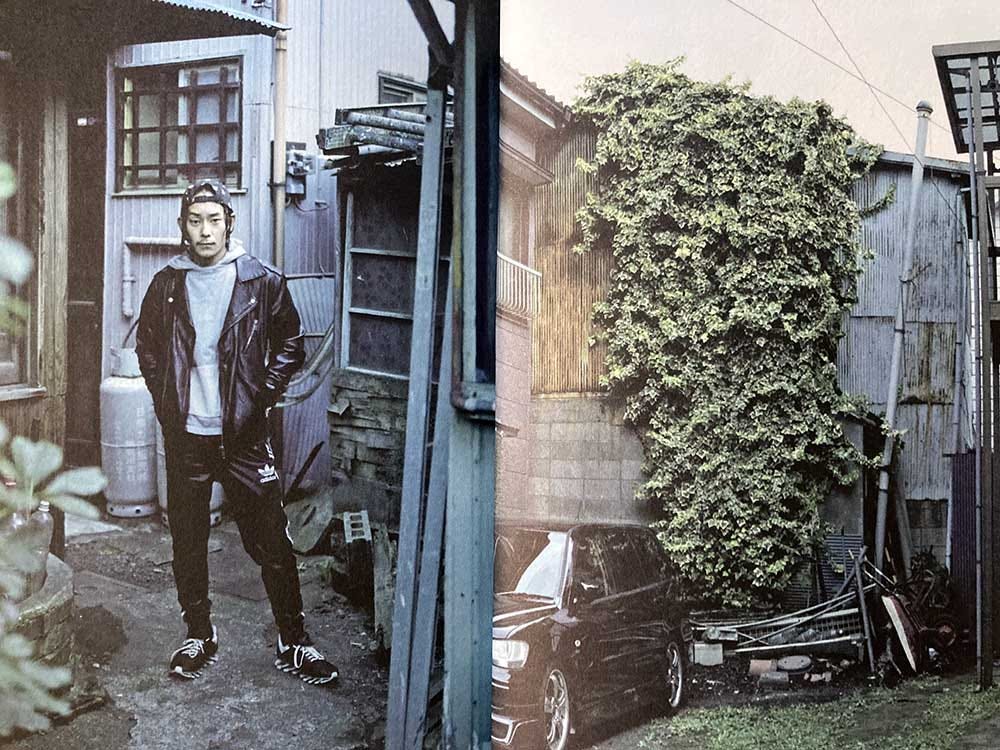

Oppenheim imagined her hero transforming a scandal-free tea cup with the thickness of animal hair. Photographer Mayumi Hosokura 細倉真弓, on the other hand, pictures heroism as something interstitial, imagining the hero of her story caught between thicknesses of skin. Her photographs that accompanied the book Kawasaki Report『ルポ 川崎』by Ryu Isobe 磯部涼, 2018, describe young people captured on their own terms. The Tokyo Photographic Art Museum group exhibition “Things So Faint But Real”, 2019, cast the city exposed to all manner of change as the hero bottling uncertainty while pressure grew in this transient part of town. Gallery spotlights picked out each photograph on the wall, vibrating as they highlighted a face or suburban part of town. Perhaps those lights held their own nervous excitement, for what the Irish poet Seamus Heaney said of working in the edges of the day and night. Writing was his way of digging to discover and unearth his heritage and upbringing with words of a nervous energy. “[I’m] a product of both” he said. “Let's try to marry them.”

The making of works … occurs in the edges of your life, in your spare time, you’re late nights or early mornings. I wanted to come at the business of poetry with a grown man’s attention, not to make it a job but to try it as a life for a while. I think that there is one kind of poet whose action is to dig in, to discover himself … an archeology of the imagination, digging up the past. If you’re involved with poetry you’re involved with words. And my words, words for me, seem to have more nervous energy when they are touching territory that I know, that I live with … I think of [the Irish landscape] as a place that I know. It’s ordinary and I can lay my hand on it and know it and the words come alive and get a kind of personality when they are involved with it for me. In other words, the landscape is image and almost an element to work with, as much as it is (or more than) an object of admiration or description.

Life on the wrong side of town 2

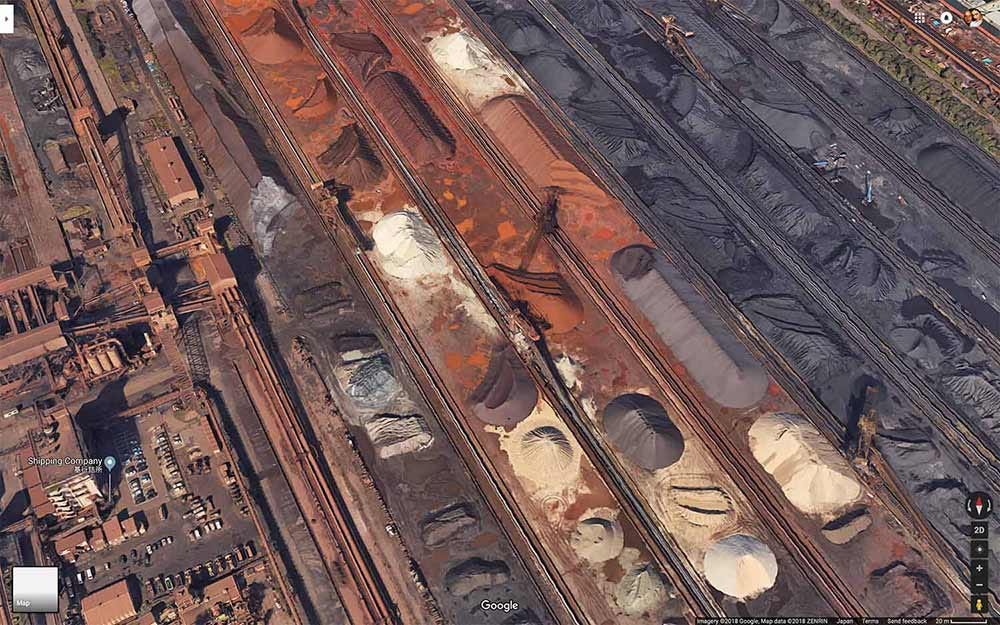

Hosokura’s photographs, taken in and around Kawasaki city, east of Tokyo, follow writer Isobe in the edges of present day Japan. Kawasaki has fueled regeneration on the banks of Tokyo bay and the Tamagawa river for decades, sites of heavy industry far from watchful eyes and difficult to visit by foot. Several incidents of arson and teenage murder threw a spotlight on problems of poverty, an aging population and racial prejudice. Isobe wrote a weekly column for a gossip magazine that formed the basis for “Kawasaki Report” and paired his works with photographs by Hosokura. We never fully know who the people in each photograph really is, where they’ve come from or where they’re headed. We only see photographs for what they are, characters emboldened by the attention, their misfortune or even their sudden euphoria.

Spotlights also animated each wall like search lights. They drew attention to the smallest detail, easily missed in dim light while a thin screen nearby showed film from a Chinese nightclub; the edge of one euphoric setting flanked by another a world away; a Kawasaki river bank, boxing gym and rave in the guts of an abandoned building. The sense urgency and purpose in each image with a nervous fervour drew a hopeful straight line between these two parallel realities in China and Japan, just as frames chopped through photographs or light outlined the slightest detail on each wall.

Cities are lonely places. “Kawasaki’s problems are not other people’s problems” read the press release, but it seemed like an odd thing to say; slightly dismissive but true to a certain degree. Read differently it revealed a deeper sense of responsibility to describe the realities of Kawasaki compared with the rest of Tokyo, different to the way they had been described in popular culture. The city is a problem witnessed daily, extended out towards Kawasaki by the banks of the Tamagawa estuary. The banks are filled with hope and apprehension, camaraderie and uncertainty, fear and loathing, adolescence and violence. Newspaper headlines filled with stories of poverty and murder are almost synchronized with the tide. The edge of peoples lives twist and turn like a river, filled with anxiety, plagued by the past and thoughts of what lies ahead. But the images possess what Irish poet Seamus Heaney called a nervous energy, touching a recognizable ground shifting restlessly with each hopeful photograph. “These photos are offered up for the youth of Kawasaki”, noted Hosokura.

Elective memory

Sung Tieu

Memory Dispute, 2017 (link)

22:42 min, HD video and sound

Cosmetically changing the body against a place with it’s own experience of cosmetic makeover was the landscape and lifestyle of Sung Tieu’s film Memory Dispute (2017), where illicit chemical skin peels enhancing appearance echoed a land irrevocably altered by chemical bombardment. An idea of self is renewed as skin is daubed with acid, allowed to dry and then peeled to reveal a whiter skin colour. A thin membrane of skin from the young person in her film is delicately drawn back, in spite of it being illegal and against a culture that has very specific ideas of gender and equality. The camera pans across waterfalls and a rainforest enclosure interrupted by the entrances to caves and secret tunnels; these were the remnants of resistance and physical scars from the Vietnam war. The scene then jumps to a bright white room with a pair of hands wrapped in latex preparing the bare skin of a young patient. Words and images pair personal territory with the forest floor, with “aesthetic” beauty salons and this elective surgery forbidden by law now taking place in secret. Landscape is an image working in private, intertwined with the body and ghosts of past conflict. This bodily landscape is much more than a form of “admiration and description”. The body has been weaponized.

The South East Asian rainforest was permanently altered by the Vietnam War, torching through the jungle with liquid napalm and causing illnesses with a defoliant of Agent Orange. In a sense, this skin treatment mirrors the values of one country thrust upon another, turning one ecosystem upside down by a proliferation of other culture. Colonialism in all forms reverberate with the same nervous energy. Shedding skin questions the image and nature of a mixed cultural background, leaving one past behind, for another raw, uncertain future. The film was part of Tieu’s multi-media installation “Coral Sea As Rolling Thunder” at Art Basel Statements (2017) that took its title from the naval aircraft carrier USS Coral Sea and Operation Rolling Thunder, weapons in a campaign of mass destruction during the Vietnam War, now used to describe the war one wages against oneself.

Tieu investigates the shifting economies of the use of toxins in past and contemporary Asia. Memory Dispute captures a remote rainforest in central Vietnam, an area heavily attacked by napalm during the Vietnamese American war. The footage recording ghostly images of an ecosystem now irrevocably altered. The landscape becomes a metaphorical study when contrasted with footage, which meticulously document the process of an illicit skin whitening treatment prevalent throughout Southeast Asia. An acid fluid is applied onto the body to separate two skin layers, allowing the entire first surface layer of skin to be peeled off. Skin, the protective surface of the body, functions here as a metaphor and a means to inquire on the circulation and shifting impact of these external forces onto individuals.

Tieu’s moving image work maps disparate and converging lines between the inflammable liquid napalm and that of an acid skin peel, exploring the body, nature and Vietnam’s layered historic colonial legacy as a vessel exposed to harm and self-harm and wider implications to future uncertainties.

From the tropics to transformation, Tokuko Ushioda 潮田 登久子 has asked what it means to retell stories of colonialism though ordinary objects as a female photographer. Her long term photographic project BIBLIOTHECA (2010) 3 has been slowly pieced together in places as far away as Macau. Between each fragment is a piece of information no less illicit than peeling away a piece of your own skin. In once instance she uncovers a family secret as well as stories of colonial occupation that have faded over time. Ushioda rushes to document these before they disappear altogether, rescuing not only a social document but freeze-framing a part of herself in the process, unaware of her own past.

The female voice is rendered through books displayed and photographed as found objects. Libraries and pubic collections become bear all their marks of a weathered, secretive past unearthed with the care of an archeological dig. In some cases books and paper have withered away, weather-beaten or eaten by insects. Shot over the course of two decades, BIBLIOTHECA (2003~) is what it means to be patient and resilient amid the pursuit of something barely visible but very real. As objects, they tell another story as the boundary between the personal, the private, and the illicit intertwine. Her notes below describe several back stories chancing upon a family secret in one and a colonial history in the other.

#19 — The 1952 diaries of novelist Toshio Shimao, kept hidden from his wife Miho. I discovered it almost rotted away in a trunk, twenty years after Toshio’s death. Cleaning up the Amami Oshima home of Miho, my mother-in-law, after she died, while upstairs I lifted up a flat cardboard box of the type used to store men’s formal wear, and finding it surprising light, slipped it open. There I spied a few university exercise books crumbled beyond recognition; pieces of writing paper with something written on them, and torn fragments of what seemed to be letters. Overcome by a feeling of seeing something forbidden, as if some awful time from the past had been sealed in the box, I hurriedly closed the lid and called out to my husband Shinzo, who was working downstairs. The box contained among other things the 1952 diaries of my father-in-law Toshio Shimao. These were the diaries my enraged mother-in-law was thought to have made him throw out, after they revealed an affair.

#20 — In the window of a termite extermination business was a hunk of book ravaged by termites, intended to show customers the havoc these bugs can wreak. Each time I passed the place, I pondered asking to take some photos inside, but they always seemed to be closed. Then one evening just before dinner, as the sun was starting to go down, I found it open. Heading inside forthwith, I asked the person sitting there eating their meal if I could take some photos. They replied that it would be closing time in half an hour, so I’d have to complete shooting by then. Grabbing a taxi, I hurriedly picked up my friend Wu-san, who lived nearby, backtracked to my usual lodgings at the hilltop Hotel Royal Macau, gathered up my camera gear and dashed back to the termite business. Perceiving our urgency, the taxi driver channeled his inner racing driver, speeding through the narrow streets of Macau while Wu-san, my husband and I wordlessly loaded film into the camera, assembled the tripod, and so on, filling the taxi with a series of mechanical clashes and clicks like the cocking of firearms, as if we were about to launch an assault on the enemy. Having got my wish and completed the shoot, we were just walking back toward the noodle restaurant at the Lisboa Hotel when the casino illuminations began to light up the main street in brilliant, bewitching fashion. Shot in 2010 at the Termite Prevention Farming Technology Company, Macau.

Tracing a line back through Kawasaki, through the complex of slag heaps, smelting plants, and glassworks, it occurred to me this shifting earthwork facing Tokyo Bay could actually bookend a more optimistic are rather than a troubled one. The line celebrated a vibrant community almost completely ignored beyond their purview. Heaney’s prose from “Digging” from Death of a Naturalist (1966) built upon his own absent landscape just as Hosokura’s photographs offer up a more hopeful view of what traditionally is seen as outsider territory. The focus was not characters and wistful storytelling but what is really happening at the fringes of these people’s lives and places struggling to be recognized as real.

Tieu threads her own line between violence and emollient, permanently altered landscapes, pummeling the body to alter the aspiration of appearance. The body becomes the ultimate battleground, waging war against an image of the self. Territories of land, mind and body intermingle while the past and future fight for control of present-day territory. Image making is a form of demarcation. New Skin, Kawasaki, Memory Dispute and BIBLIOTHECA all take a particular points of reference to speculate the wider role of storytelling. And although using science and fiction to also tell another story, Le Guin suggests the story is less a mythological genre than a realistic, believable one.

The heart quickens and the mind races. “Digitalis or First-Person Camera,” curated by Hosokura and featuring work by Umi Ishihara, Maiko Endo, and Yokna Hasegawa, now suggests the boundary between each of us is skin deep. How we bottle our worldview as distinct and different depends on the way we picture it and the other untold story of uncertainty. The problems of Kawasaki or other parts of the world may not be other people’s problems or even responsibility, but we *all* live in disturbing times and should at least be empathic to their conundrum. As Donna Haraway puts it, staying with the trouble requires learning to be truly present. Nervous words and new skin bear witness to this, reimagining those boundaries that keep others out, regardless of who or what the other is.

Recommended:

“Digitalis or First-Person Camera | Umi Ishihara, Maiko Endo, Yokna Hasegawa, Mayumi Hosokura” at Takuro Someya Contemporary Art (Apr.17–May 29, 2021)

– Curated by Mayumi Hosokura

Past issues:

1. Burn it Down, Build it Up

2. Positive entropy

Donna Haraway, “Receiving Three Mochilas in Colombia: Carrier Bags for Staying with the Trouble Together.” In Ursula K. Le Guin, 2019. The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction. Ignota, p.10.

Daido Moriyama: Terayama (MxM/MATCH, 2015) contains five of the seventeen essays by Shūji Terayama that make up Supōtsu-ban uramachi jinsei (“Life on the Wrong Side of Town: Sports Edition”) which originally appeared as a series in the magazine Mondai Shosetsu (“Problem Novels,” published by Tokuma Shoten) in 1975 and was then published as a single volume by Shinhyosha in 1982, the year before Terayama passed away.

BIBLIOTHECA #19 and #20, 2010 in ‘Anneke Hymmen & Kumi Hiroi, Tokuko Ushioda, Mari Katayama, Maiko Haruki, Mayumi Hosokura, and Your Perspectives’ at Shiseido Gallery (Jan.16–Apr.18, 2021)