Red dots

It lasted less than a minute and then it was gone.

The eye exists in a wild state according to Andre Breton, leader of the Surrealist movement and a man known for his distrust of otherness, who threw the Swiss sculptor Alberto Giacometti out of the group for refusing its strictures. I’ve been reading accounts of Giacometti’s life in Paris from 1922 until his death in 1966. By all accounts he was hardly an enthusiastic member and gravitated towards Surrealism on account of friends who lived in Montparnasse district of the city, a gang more interested in rejecting real things in the hope they might achieve new heights of imaginative, intellectual freedom. It was ‘catching’ reality not rejecting it, as historian Michael Peppiatt describes, that drove Giacometti to make some of his greatest work even when the real things, the figures, characters, and infatuations he chased after were always moving and impossible to pin down. Having arrived in the city and then fled its German occupation, frantically burying work in his studio floor before unearthing it on his return to find his studio just the way he’d left it, it’s clear how to see how the world now as then instills a sense of panic staring back with the same ferocity. Might Breton’s ferocious eye picture that world with all its tolerated cruelty as surreal?

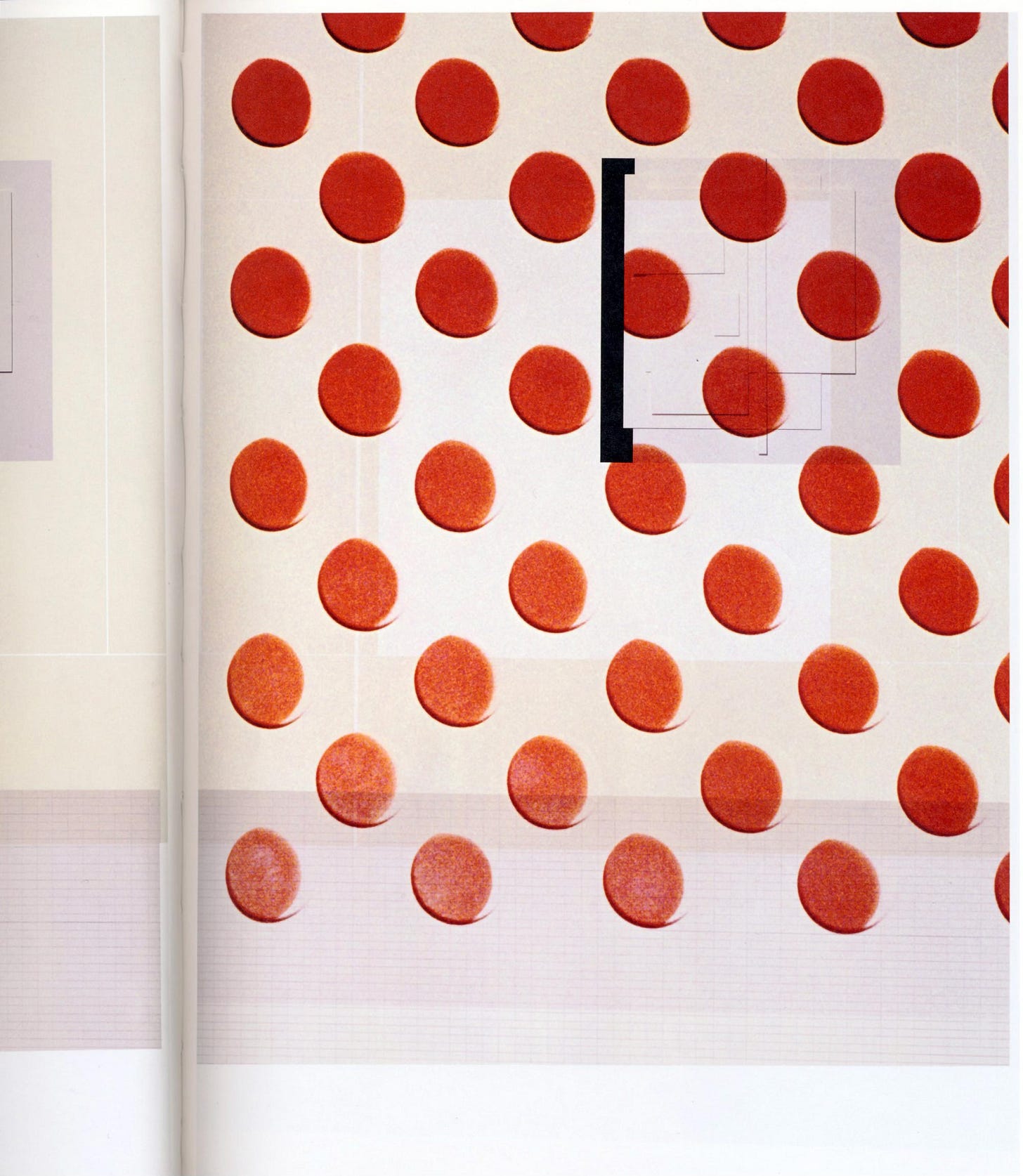

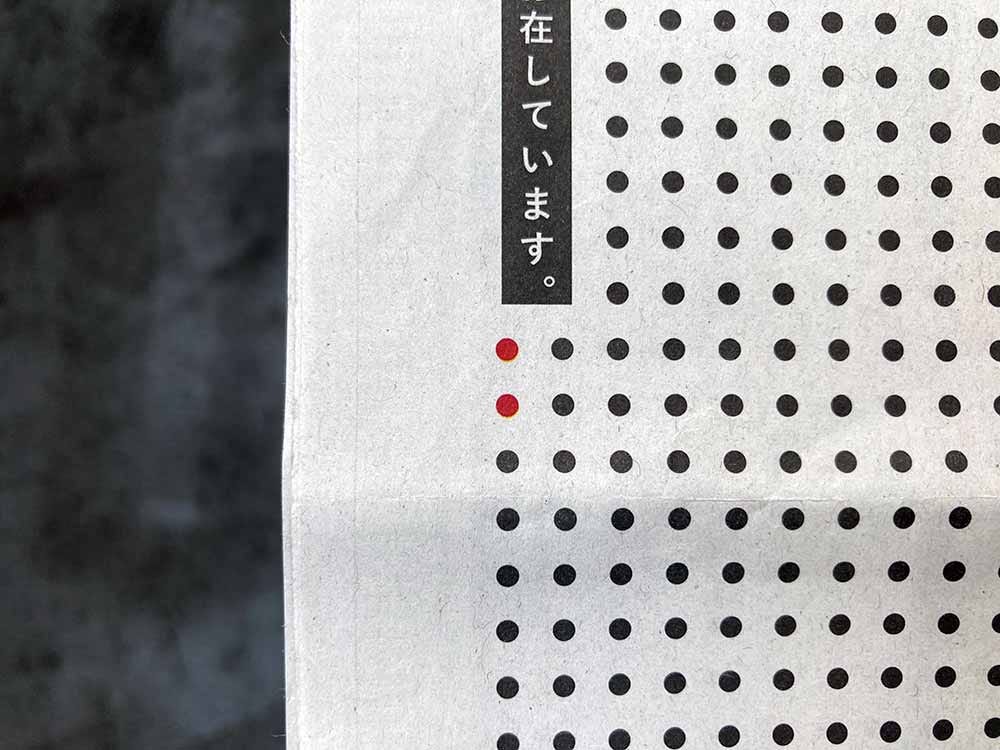

I started writing this unfinished post four years ago covering a complicated mix of relationships all about digging up and digging into humour laced with shock. There was artist Michael Dean reflecting on growing up on council estates in the 1980s with concrete the material world he knew best. The there was the art director and graphic designer Hideki Nakajima who I had met a month earlier and image above comes from his monograph published in 2021.1 There was also a copy of that month’s Nagasaki Shimbun newspaper dated August 9th, marking the atomic bomb dropped on the city following the bombing of Hiroshima three days earlier in 1945 — its broadsheet center spread still takes the breath away while also appearing strangely distant and detached. As reading material goes, the detail of those two days reduced to a grid of dots becomes terrifyingly blunt.

Blunt and direct material for Michael is concrete. Under the stairs and by the fire (2021) at Mendes Wood DM in Brussels pictures a life surrounded by hard surfaces. Growing up as a kid in the 1980s was a physical mental endurance, a test of wit and cunning where language navigated adolescence and its school of hard knocks with words liberally and literally pulled from the street. Words said in the heat of the moment are tossed around, like “Fucking mortal” and “LOL” (Laughing out Loud) now scrawled across concrete columns that stand or slouch in the gallery and former house. In the right light they look key-like as if able to unlock a treasure trove of adolescent secrets. Words as weapons may as well be made from sand and cement. “Concrete is just really cheap,” he says at point, choosing his words carefully. “It’s also stupid. Perhaps in a punk sense, fuck you. All I need to do is mix sand and cement with a bit of water and now I’ve got something that is so categorically solid you can’t argue with it.”2 Violence is a stupid language, the fist fight another form of wordless communication. Writing is a way of holding onto moments of intense attraction only to let them go when words are married and transformed into something else, digging in to know them better and pull something positive from a brutal past.3

Under the stairs and by the fire closed mid way through the summer of 2021 with an image of concrete as sensitive and solid, but cement burns the skin as easily as it turns sand and water rock hard and while fusing opposites can release a flood of ideas splitting them unleashes all manner of unknowable terror. Before the world’s first Trinity test detonating the world’s first nuclear device deep in the New Mexico desert of White Sands, scientists wondered whether exploding their so-called “Gadget” would start a chain reaction that might spiral out of control. Physicist Enrico Fermi even teased fellow expert Edward Teller, who feared the worst, by taking bets on whether the earth’s atmosphere would go up in smoke.4 The August 9th 2021 edition of the Nagasaki Shimbun newspaper marked the 76th anniversary of the atom bomb ‘Fat Man’ dropped on the city in 1945 three weeks after the White Sands’ test and a mere three days after the first bomb ‘Little Boy’ had been dropped on Hiroshima. Nagasaki Shimbun replaced all of its usual reporting with a centre spread of dots, each representing a nuclear weapon stored somewhere in the world. This dry uninterrupted graphic swallowed every other piece of news that day, referencing the second world war amid the then pandemic with a sublime vision of fear and understandable loathing. Two dots were picked out in red amid the newsprint placed carefully place below the masthead, one dot representing Hiroshima and the other representing Nagasaki — the only two cities to have felt their full power. On the reverse are maps of Nagasaki before and after the bomb with histograms, bar charts and pie graphs explaining each explosion in detail. Looking at that paper now, I can’t help but think of a post-Surrealist Giacometti hankering after the real world and the futility of catching all of its intensity, having struck up a friendship with Picasso who in 1937 had just finished painting the bombing of the Basque town of Guernica in furious protest.

So back to the street and concrete urging us to speak up, back to writing about people with nerves of steel and new skin, youthful opportunists leaving home in search of inspiration, and the strange coincidence of the summer and Members of the World Show witnessing past conflicts transform into endless wars. The top image by Hideki Nakajima was first show at Graphic Wave in 2000 at Ginza Graphic Gallery celebrating unorthodox art direction that welcomed in the new century. His Unfinished series is a nod to that unorthodox approach which still kicks against convention. Whereas other designers of his generation channelled their disillusionment with culture, Hideki remained firmly lodged in the brain without any overbearing sense of sadness or madness, for that matter. If Micheal is liberating language from nostalgia, Hideki refutes is altogether removing every trace of sentimental language to leave pure image in its place. Hideki Nakajima passed away on February 3rd in 2022. We met the previous September thrusting magazines into my hand, with him leaping up to show me old work and his newest book. We talked for ages and, for some strange reason, he urged me to start a food vlog. Afterwards we stood outside against his International Klein Blue studio wall and had our photograph taken. This generous man with a rare talent for rebelliousness, for doing things differently and rubbing people up the wrong way was as kind as kind could be. He passed away before we had the chance to meet again. Several days after his death I was walking through Ginza when all of a sudden it started snowing. It lasted less than a minute and then it was gone.

Hideki Nakajima, MADE in JAPAN (Tokyo, 2021) https://nkjm5430.stores.jp

“Concrete is like my material world. I grew up on a housing estate that is made of concrete and living our lives against concrete surfaces. That’s my material. This idea of wanting to turn my writing into a natural world, concrete was the material with which to manifest (it). There is an idea of democratic ceramics [“using materials that we all have had access to.”] Concrete is just really cheap. And it’s also stupid, perhaps, in a punk sense fuck you. All I need to do is mix sand and cement with a bit of water and now I’ve got something that is so categorically solid you can’t argue with it.” Michael Dean [link]

Seamus Heaney spoke to Patrick Garland about the craft of poetry first aired in 1973 https://www.bbc.com/videos/c9xz2l380x9o