Two paintings by the same artist. One of a technophobe and the other a technophile. Seen all of a sudden, they described skepticism and a passion for the unfamiliar in a flash, scanning skin and staring into space. But seeing them now in the flesh was like crossing some strange boundary where the world took a turn for the surreal. All I wanted to do was sleep.

I’d arrived in Kyoto the day before and by 4:30am the city had been wiped clean by passing weather and a mood that had been building. I was drenched in sweat with eyes wide open, ripped from sleep by the memory of past injections and the looming threat of another. The old Imperial palace could be seen from the window at the foot of my bed. Street lamps bathed tarmac in Orangeade with a silhouette of Mount Hiei in the distance. I planned to head home that day but not before stopping by the Museum.

The museum had been bought by the ceramics manufacturer Kyocera (Kyoto-Ceramics) and renamed the museum in its honour — the Kyoto City KYOCERA Museum of Art. Buried within a catalogue was Smallpox vaccination (1934) by Ōta Chōu (1896-1958) a Japanese painter of nihon-ga from Sendai in the North. It featuring two women whose faces were crossed with vague concern. A doctor sits to one side facing their patient with eyes trained on her steady hand. 1 However, the white interior and green obi sash couldn’t be more different. Black modern darts shooting up and down are drawn like daggers across the modern girl’s kimono as a bifurcated needle is pushed softly through the skin. It reminded me of seeing an image of Women Observing Stars (1936) another painting by Ōta stored at Tokyo’s Museum of Modern Art, MOMAT. 2 This also features someone seated peering through the eyepiece to telescope but now she is surrounded by figures more interested in her than what she’s looking through.

The paintings and people ignore the tools they operate to suggest an introspective concern; who are these modern people? Blank stares run alongside curiosity for the future. Eyes stare down at tools which point upward. But the women in his paintings are lost even with the tools at their disposal pointing aggressively at a future, however uncertain. One woman risks convention with her face trained on what the telescope can see but we can’t. The barrel obscured her face and her dress is the only thing to stand out and the only one to feature wildlife. The spectacle they create takes over as the woman obscured blends with the background like a bird in a tree. The sash wrapped around her waist is all that stands between her and obscurity, replacing her stare with an image of collective curiosity and hope.

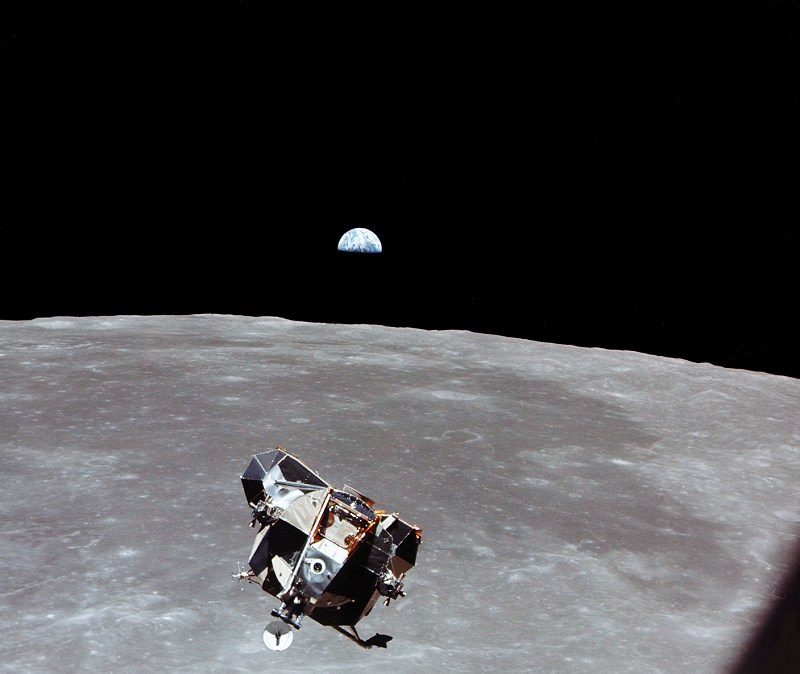

It’s hard to say whether each of these relate to today in any way, to our current fear of the novel coronavirus or the impassioned risk of wealthy recreation, leaving Earth for low Earth orbit. Society has simplified its relationship with the world to the extent that leaving to look back and see the planet in one go seems less absurd than safeguarding the self against invisible and unknown threats. That Earthy overview becomes nostalgic, looking back and turning inward. The famous Earthrise photograph taken by astronaut Bill Anders aboard Apollo 8 on Christmas Eve 1968 gave the first complete view of the planet. Yet it also reduced the expanse and endlessness to a mere blue dot in the sky. 3 The moment the world stared down at its own (in)significance also marked it pushing at the limits of its own potential.

At first, NASA and the CIA denied the photo existed. It wasn’t until writer and counter-culture figurehead Stewart Brand pointed it out that its existence became public knowledge, gracing the cover of his Whole Earth Catalog (1968-1972). “It could be said that the psychology of machines begins when humans are more machinelike in their actions than the machines they employ” said Normal Mailer in Fire on the Moon (1969).4 Mailer had witnessed the preparation and unfolding drama of the Apollo 11 mission in July, 1969 reporting for LIFE magazine. Mailer grew frustrated with the lead astronaut Neil Armstrong who only ever talked of the technical challenges that awaited them. Any personal space remained impenetrable. Mailer saw Armstrong as embodying the tension between composure and chaos when staring fear in the face. Armstrong landed on the Moon the year after Anders’ photograph and previously flew F9F Panther jets from the deck of USS Essex during the Korean War. At 500 ft above the Korean peninsula he flew photo reconnaissance with eyes were trained on the instrument panel in front of him instead of the ground mere feet below. Imagining the world at such a scale required a certain sense of self-denial and disregard.

Obscured faces read like curiosity tethered to the ground. For the women in Ōta’s paintings, that curiosity is earthbound or under the skin. Staring at machines for what they do not what they are suggests an awareness of something happening in the background. They are tangible and immediate but still a mystery. Disembodied, the filmmaker Toshio Matsumoto weaved voices from a Kyoto factory with the image of children playing in the shadow of a silk house in the 1961 documentary The Weavers of Nishijin. At some point a voice is heard from out of nowhere describing the scene. “They do not understand the invisible forces at work, yet they can see them.” 5

Unlike postwar nihon-ga paintings by Mikami Makoto and Hoshino Shingo, members of the Pan-Real Art Association who would grapple the wartime experience, Ōta came to being before the war ever reached his own shores. Modern society, he noted, was cool and detached, so rendered it as flat and shallow.

As if reflecting on Ōta’s image of Modern Japan, photographer Takuma Nakahira remarked years later how “we gaze at things and lunge at them … things are constantly in retreat … [and] the gaze of [these] things is cast back.” Staring into the abyss only for it to stare back as a reminder of who we. Every line and detail appears oblivious. Tensions in both Smallpox vaccination (1934) and Women Observing Stars (1936) erupt despite the tussle of modern society appearing neutral, between the inner world of a conservative culture and the outer reaches of a radical avant-garde. These two paintings picture machines with a will of their own and the natural world as comatose by comparison.

The women Ōta paints map the then modern world, of medicine and machines conquering the body escaping the world. Throwing caution to the wind like throwing daggers at stars in the hope they hit something describes the shift in modern society, between the stars and vaccines that are out of reach and out of sight. Porcelain and precision instruments, etiquette and industry, war and photography, composure and chaos, shooting for the stars then skimming the inner atmosphere; threading these invisible things together with the hope they help prevent hardships from unravelling any further. For a day and a half both of Ōta’s paintings showed fear and passion in equal measure. It remains to be seen whether this would make any difference to them or me in the long run. For the time being it was clear that a bad night’s sleep in Kyoto had helped focus attention for a brief moment, away from the individual toward somewhere else, conquering new worlds and escaping myself.

Recommended:

“Don’t Send Robots Into Space. Send Embodied Curiosity,” ArtReview, October 2021 [https://artreview.com/a-shot-in-the-dark-whole-earth-2021/]

“Celestial Nobodies” ARTnews, October/November issue, 2021

[https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/tokyo-art-exhibitions-eri-takayanagi-makoto-aida-1234605192/]

“Clear Intention: Art Collaboration Kyoto,” Art Asia Pacific, November 25, 2021

[https://artasiapacific.com/Blog/SponsoredArtCollaborationKyoto/]

“Toshio Matsumoto: Everything Visible Is Empty” at Empty Gallery, Hong Kong Sept.9-Nov.18, 2017 [link]

Past issues:

1. Burn it Down, Build it Up

2. Positive entropy

3. Nerves and New Skin

4. Wish you were here

5. Zone Tripper

6. Members of the World Show

Kyoto City KYOCERA Museum of Art Collection

https://kyotocity-kyocera.museum/en/exhibition/20210320-20220313

MOMAT Collection

https://www.momat.go.jp/english/am/exhibition/permanent20211005e/

“Don’t Send Robots Into Space. Send Embodied Curiosity,” in ArtReview (Online: 5.11.2021) https://artreview.com/a-shot-in-the-dark-whole-earth-2021/

Norman Mailer, A Fire on the Moon, Penguin, London (2004:108)

“Everything Visible Is Empty: Toshio Matsumoto,” Mousse Magazine (Online: 31.10.2017) https://www.moussemagazine.it/magazine/everything-visible-empty-toshio-matsumoto-2017