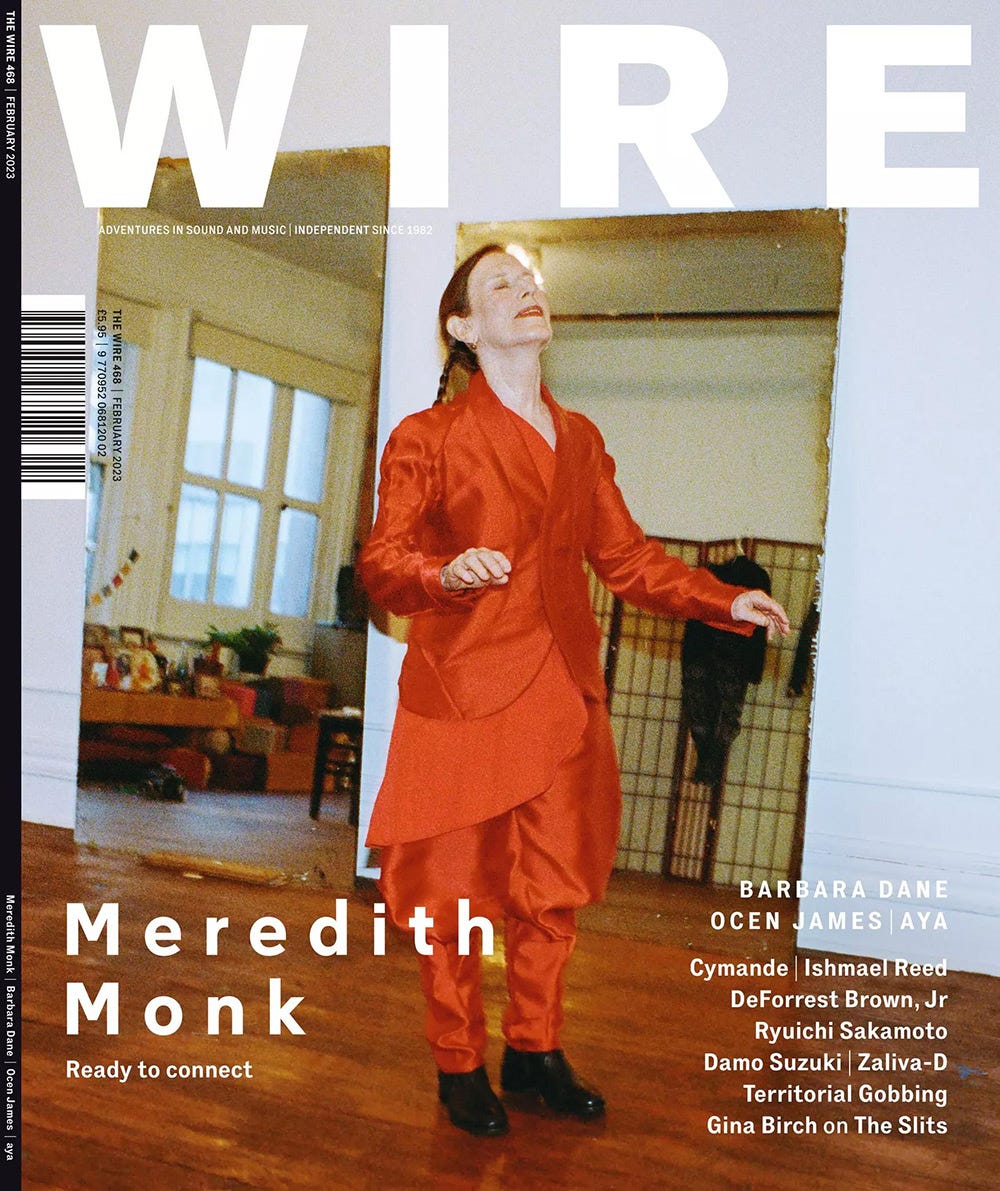

Hi there. Comi Comi returns in 2023 with not one but two pieces on the artist Shinro Ohtake. The first was written late last year for Art Basel.1 The second appears in the latest issue of The Wire magazine — get a copy if you can and support independent publishing at the same time.2

Late last September I travelled 700km south of Tokyo to visiting his studio in the hills surrounding the port city Uwajima. The visit also brought me back to London with the memory of a mutual friend who had passed away several years before. Odd weather from the recent typhoon had forced the river outside his studio to swell and filled his work room and warehouse with thoughts of Wandsworth and South London. The weather only cleared when we talked about home. Shinro had knocked on a door in the UK during the early 1980s that I later visited twenty years on, my knock welcomed with a film by the Quay Brothers and a bottle of whiskey. Now at Shinro’s door, the mutual friend was part of our sharing stories.

The second, smaller piece was written for this February edition of The Wire magazine. Shinro had lived in London at points throughout the late 1970s and early 1980s, when punk had first emerged and then when punk had all but disappeared. Uwajima was his new home, quietly removed from the rest of the Japan, away from the railway that threads through the Ehime countryside, looking out to sea. Pulling in to Uwajima, with Tokyo a distant thought, the port city and final stop on the line would scream with its image of palm trees and empty streets as I left. The same station appeared in Tokyo the following month, this time in the shape of a sign that read ‘Uwajima Station’ signalling his current exhibition. The same signage now flashes at night as the exhibition is almost over (February 5th). From there it moves to Ehime Museum of Art and a short train ride from Uwajima. Heading home.

Thanks for reading.

In the studio with Shinro Ohtake (Art Basel)

In the first few days of September, Uwajima Station (1997) hovered over Tokyo’s MOMAT, the National Museum of Modern Art. The signage glowed red at night, teasing the forthcoming exhibition of the Japanese artist Shinro Ohtake, his first major retrospective in 16 years, its four characters creating a link between Ohtake’s rural home and his birthplace, Tokyo. The real Uwajima Station can be found some 700 kilometers to the south, at the mouth of Japan’s inland sea.

Ohtake is one of the most recognizable artists of his generation, yet also one of its most elusive. He thinks of himself as an outsider, having moved to Uwajima to escape his compact Tokyo workplace more than 30 years ago. But having lived abroad too, the capital also felt more or less like any other city he had lived in, he says. Moving away proposed the freedom of working differently, at an unimaginable scale, so he took his experiences of traveling the world and transposed them with an altogether different vessel: His first sculpture would be made from parts of an old wooden ship found in Uwajima.

This year’s retrospective at MOMAT, titled simply ‘Shinro Ohtake’, follows these obsessions and more across some 500 works spanning collages, scrapbooks, kinetic sculptures, and noise music. There are his ideas of self and otherness, dabbling with fabricated memory, organic dreams, layers, sound. Furious sketchbooks erupt in scale and color as the damage and distress of paintings express a nebulous view of visual culture, indiscriminate in how things are absorbed, then discarded. Commenced in the 1970s, Ohtake’s series of over 60 scrapbooks are sculptural objects, with pages collaged with images drawn from American comics and magazines to receipts, flyers, and tickets from the artist’s travels. On occasion Ohtake scales that practice to architectural dimensions, as with the prefab summer cottage-turned-audiovisual scrapbook, MON CHERI: A Self-Portrait as a Scrapped Shed (2012), which was commissioned for documenta 13 in 2012 and installed in Kassel’s Karlsaue Park. While the work responds to the 2011 Tohoku earthquake, tsunami and Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant disaster – steam rises from the shed – its title, MON CHERI, appears in the more angular Japanese katakana script on neon signage taken from an out-of-business snack bar in Uwajima.

Uwajima Station is the very last stop on a line that cuts across flat land and through mountains. The small port city is met by a fanfare of palm trees that lead toward the bay of oyster farms and, beyond that, the Uwakai Sea. Ohtake’s studio is a 15-minute drive away, along a narrow stretch of road winding through the valley. The weather is warm, blue sky peeks through clouds. This is as far as one could be from Tokyo – a place where Ohtake is simply known as Ohtake, ‘the artist.’

Born in Tokyo in 1955, he dropped out of Musashino Art University to work on a Hokkaido dairy farm, then left Japan and moved to London in 1977 before returning to school. London proved pivotal: Punk had just happened and by the time he left it was nearing its end. He came across a man selling handmade matchbook and cigarette boxes at the city’s Portobello Road Market, which seeded ideas of recording, rebuilding, and remembering everyday things in an unplanned, unscripted, and unconventional fashion. Once back in Japan, he founded the experimental noise unit JUKE/19. (1978-1983), which treated sound and image as one and the same, while Only Connect, a sound unit formed with the artist Russell Mills, a lifelong friend, trod the path of improvisation in 1985 as the opening act for the rock band Wire.

As extraordinary as this all sounds, Ohtake describes this last period as slow and unfocused, balanced only by taking each day and capturing it with his 8mm camera. When we meet finally at his studio, it’s clear he still values that daily process. ‘It’s proof of my existence. Without that, I would just fade away.’

‘UCA’ (Uwajima Contemporary Art) is spray-stenciled on the door to his work room. Despite the institutional title, he works alone. There are piles of archive boxes and vinyl littering the floor. One whole wall is filled with filing, interrupted by the odd found object or piece of art. There are photographs of Mills setting up a London show in the mid-1980s. One photograph by Ohtake shows David Hockney on the phone, his back to the camera. There is even one of Hockney’s ‘joiner’ photo collages, of Ohtake and friends from the early 1980s, hanging beside it. Surveying the expanse and the wide staircase upward, it’s hard to make sense of everything. It’s just more of the same, Ohtake says, shaking his head. ‘I don’t want to think about it.’

We walk back through a courtyard of bric-a-brac to his main studio, a more relaxed space, like someone’s living room. Catalogues, brown paper bags, and music are all strewn across the room. A leather sofa is crammed into one corner, facing a stack of works against the wall. His piece Retina Table (Ambleside) (1991-92), a timber and resin plinth made from the fiberglass mold of a ship and covered in found photographs, is sitting on wooden chocks. There is even a miniature model of the studio hovering, oddly surveying the inside of itself. Other corners are filled with cans of paint or works in progress, or they serve as artwork storage. That first sculpture made from a wooden ship now sits on the floor wrapped in plastic. But of all the works to feature in his upcoming retrospective only one remains, waiting to be collected. Mnemoscape 0 (2022) leans against a wall between this studio and another, its uneven surface of cardboard and cigarette paper covered with crimson pinks, glitter, and black paint.

There is no need to think about what to ask Ohtake. Mnemoscape 0 and every other wall contain a conversation. His time in Europe is reflected in posters for the German punk band D.A.F. (Deutsch Amerikanische Freundschaft) and his first overseas show in 1985 at London’s ICA, alongside the painter and installation artist Tim Head and the American photographer Duane Michals. It’s a nebulous haze of culture, canvas objects, and sculpture, all being reorganized or remade. He claims to never plan or sketch anything. Instead, works appear from scratching away at what’s already there. And the question of ‘why’ is also of little interest; he simply makes.

With moments to spare he pulls on a printed roll of tarp that bears a collage used at Dogo Onsen, Japan’s oldest hot spring, in Matsuyama. Netsu-kei (2021) will wrap the onsen building until its renovations end in 2024. Ohtake also feverishly mentions a new record from his band Puzzle Punks, recorded with the multidisciplinary artist Yamantaka EYƎ. Their last album was released the same year as his first major retrospective, ‘Shinro Ohtake Zen-Kei: Retrospective 1955-2006’, at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo, and featured recordings from 1996. Slow projects like these bear the most fruit.

The three hours spent in Uwajima feel like three days, and leaving Uwajima Station feels oddly bittersweet, save for knowing that Tokyo will soon welcome Ohtake back. Speaking with the artist, connections between discovery (‘there is no plan’), diffidence (‘I am not even sure I enjoy making art’), and possibility (‘I’m really excited for what happens next’) suggest someone provoking their surroundings. The restless energy of the city counterbalances the rural calm with a ravenous practice that bears little similarity to the tranquility outside. A din of ideas bounce back and forth inside, between the work room and studio, wrestling with the sensation of finding something and then having picked it up giving that thing, and idea, renewed purpose. Outside his studio, Ohtake leads the way through the garden toward a nearby river and a waiting car to catch the last train home. The greenery is recovering from a recent typhoon and the river is still a torrent of water. But while Tokyo always comes off worse when heavy weather hits, the land here bends to accommodate any sudden storm. Unnerved by the thought of being inactive Ohtake seems to bend as well, unfazed by unexpected change. So it’s not surprising that Uwajima Station appeared atop MOMAT, and will appear again to mark the opening of his exhibition there in November. It’s a signal of home that also marks an unending interest in remodeling what others discard and take for granted.

On Site: Shinro Ohtake, National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo (The Wire 468)

Past issues:

1. Burn it Down, Build it Up

2. Positive entropy

3. Nerves and New Skin

4. Wish you were here

5. Zone Tripper

6. Members of the World Show

7. Daggers thrown at Stars

8. Horizontal, Vertical, Cemetery & Sky