Members of the World Show

Lei Yamabe & Yuki Okumura versus the World

Hi there.

Another devastating summer has run its course with an avalanche of red tape and extreme weather. Lei Yamabe 1 from a partial base in Belgium had curated this summer’s exhibition “Landslide to be lived off and/or tongues to be deadpan,” 2021, @misakoandrosen, Tokyo. But it was widely known that Yamabe was also the pen name of artist Yuki Okumura.

Okumura studies other people. “The Man Who, An Ephemeral Archive” in 2019, “29,771 days – 2,094,943 steps” in 2019, “Welcome Back, Gordon Matta-Clark” in 2017, “Hisachika Takahashi by Yuki Okumura” at Maison Hermes Le Forum, Tokyo, in 2016, even “Shuzo Azuchi Gulliver & Yuki Okumura: Shi” in 2014, were all agents of his own curiosity.

His film The Man Who (2019) invited Marja Bloem, Michel Claura, Herman Daled, Michele Didier, Rudi Fuchs, Yves Gevaert, Kasper Konig, Jean-Hubert Martin, and Phillip Van den Bossche to share memories of Japanese conceptual artist On Kawara and Dutch conceptual artist stanley brouwn. Without mentioning names they simply referred to “him”, a man who was part Kawara and part brouwn.

And with Hisachika Takahashi, Okumura had found an artist whose life had also been shaped by another, having spent forty years or more as assistant to Robert Rauschenberg in New York.

For Okumura, “The Knowledge and Beliefs of the World” in 2018, was different again. He was closer in age to the other two artists, Yasuko Toyoshima and Eri Takayanagi. Reworking their texts made them closer still. At one point, Toyoshima even described a collective alter-ego: members of “the world” show.

Diffuse, the anecdotes in The Man Who (2019) were anything but descriptions of interesting or quiet people and more fragmented, pulling other characters into their collective orbit. My own fragmented situation I found myself being bent out of shape by a vaccine injection. Had my own piece of writing mimicked the reworked sentences stacked precariously like a deck of cards?

The bundle of forms crammed into an envelope were handed to the nurse who handed them back just as quickly, pulling the needle from the top of my arm. Eventually, I was ushered through a field of other patients, hot and flustered as if blown across the room by a mass of warm air. I was suffocating behind a paper mask, gasping for oxygen.

Everything fizzed with sound from where I lay moments later, recovering from surprise shock of it all. I stared at smoke alarms on the ceiling and felt as if falling backward through a hole of high blood pressure, ice cold and drenched in sweat. My tongue tasted metallic and the doctor’s warm hand sparked a gentle charge by touching the back of my cold wrist.

I left exhausted an hour later, bombarded by heat that bore into my face like a drill. Should this weather be celebrated or mourned, I wondered?

Summers were once magical. Now they felt unhinged.

“The Knowledge and Beliefs of the World” in 2018 had featured Okumura alongside Yasuko Toyoshima and Eri Takayanagi. Okumura treated their written statements as one strange hybrid, adopting parts of each person to ask whether exhibitions were really necessary. There was no real answer, just as there was no way of telling who each of them were unless you knew beforehand. For all intents and purposes they were characters as much as real people. This became my own starting point.

I had visited the show but struggled to describe it in any meaningful way. Artworks were so subtle it would have been easy to think they were just aloof. When it came to presentation, Okumura trod a fine line between himself and the other two, rewriting statements by Toyoshima, Takayanagi and the curator Tsuyoshi Ueda — Statement: Sequence (2018), Statement: Self-Observation (2018), and Statement: Correlation (2018) — by building the character of someone as the sum of other parts and other people.

Perched on hooks each text was a sheet of laser printed A4 paper mounted on double-sided aluminum, which needed gloves to turn them over. Texts were seeded with a vocabulary that he called a “landslide” of grammar ploughing through each letter. They resembled a poem and manifesto rolled into one. One side was written in Japanese with the other in English. And the combination of the two meant one or the other could happen without the need for translation.

“I am capable to negotiate the threshold between inspiration and exploitation,” he wrote at one point. Did it matter, he asked, where each set of words came from where they ended up?

It was a vocabulary shared with his a long term project, “Hisachika Takahashi by Yuki Okumura” (2016), which unpicked the life of Takahashi, an elusive artist drawn alongside the generation he grew up with. A former assistant to Robert Rauschenberg, Takahashi’s “From Memory Draw a Map of the United States” (1971-72) for instance tasked friends and contemporaries of the day, like Jasper Johns, Gordon Matta-Clark and Lawrence Weiner, with drawing their own map of America from memory.

These drawings relied as much on imagination as they did the real contours of a map. But the Komagome SOKO show involved three real, not imaginary people. Takayanagi used real objects — a pocket calculator, felt blanket, an old coffee — designed with real people in mind.

“Artists generally show what they want to behold,” wrote Okumura, reworking Ueda's quote from Julius Ceasar’s The Gallic Wars, “Men generally believe what they want to believe.” Updated, the men were now everyone. Their objects strewn across the floor and up walls resonating with realness.

Toyoshima’s Pata-Pata (2017) was a Jacob’s ladder of wooden blocks hung between the floor and gallery ceiling flipping between two-sided characters for sky (ten) and ground (chi). Her long interest in portraits were shaped by hidden forces found in the unlikeliest of places. One example not on display Mini Investment (1996–) produced a self-portrait out of thin air.

In it she bought partial shares in a nondescript company but the investment was locked and impossible to benefit from. Without buying them outright she could only look on and watch their value rise and fall. There was no financial reward, just a picture of her investment.

The uncertain market was a mirror. Checking the condition of shares became a daily routine. Each day she would check to see their value. Had it risen or fallen? She simply watched on unable to influence them in any way. The investment and auto-portrait gave new meaning to the phrase “investing in yourself”.

In one sense, Toyoshima had been reduced her self to the image of a line chart. Her character had replaced mood and feeling for stock markets around the world. With Pata-Pata (2017) Looking skyward or at the floor, Mini Investment (1996–) was time she spent staring at the share value, ‘looking’ was a way of investing in something offering something in return.

Night fell on Osaka’s Shinsekai (“New world”) as people stuffed their faces. Shuttered shops lined busy streets. Theatre filled every moment and every mouthful. Lard was ladled from barrel to boiling oil as taxis narrowly avoided a cyclist spitting wildly at the street. Faces in the crowd sent the cyclist into a flail of arms and legs, struggling to wave and stay upright. And all the while people looked on undeterred and hungry, finding it hard to digest the drama mid-mouthful. As poet Tan Lin once remarked, anticipation is an interesting and difficult thing to (re)produce.

The Big Roof pavilion in 1970 hung like a summer storm cloud at night. Lights at Osaka’s EXPO’70 dimmed as signs illuminated the expectant crowd. Their curiosity was barely visible in footage from that night now streamed online. 2 An overhead screen was filled with a succession of titles that begin, A Drama of a Human Being and Objects.

Thousands sat as stragglers weaved through the forest of legs searching for somewhere to sit. No one knew what to expect or maybe they simple don’t care. A young woman stared off into the distance, not noticing the man vying for her attention and children were drowned in the sound of everything else. Everyone seemed unaware they were equally a part of this spectacle as the event they were here to see. They were spectators caught up in the frenzy quietly influencing them.

Japan’s first official World’s Fair presented a postwar conundrum. The theme of “progress and harmony” running contrary to regeneration was not an optimism shared by everyone. Witnesses to this upheaval were artists collectively known as Gutai, a group of cultural avant-garde outliers concerned with depicting a flawed, uncertain future with humour. Their name defined in simple terms as ‘tangible’ and ‘certain’ also ran contrary to a collective conscience, eager to leave a strict past for uncertainty and freedom.

Yet contradiction was the tool (Gu) that bound a postwar world together (tai). The group’s figurehead Jiro Yoshihara no doubt sensed this early on writing in their 1956 manifesto, “the human spirit and matter, opposed as they are, shake hands”, but that handshake quickly became a tussle. At the heart of Gutai was the idea that materiality had become revenant, seeking revenge for years of unsustainable growth. Yet no sooner had infrastructure sliced through the city and the countryside that Gutai disbanded, vanishing as suddenly as it appeared and giving way to an industry of unforgiving change.

As captivating as the the Expo pavilion footage was, it pictured the promise of change in fragments. The celebration that night felt incomplete without the landscape which played host. “The Atrocity Exhibition” (1970) J.G. Ballard’s ‘condensed novel’ that year, echoed the film’s sense of estrangement. Its first chapter had also appeared much earlier in the British science fiction magazine New Worlds. This time, images were characters attempting to escape a landscape of media and tumultuous events from the year before. Navigating this turbulence meant the physical landscape had been reshaped with its own form of confusion.

Bodily clefts and landmarks looked the same. Characters who had died early on reappeared. Assassinations became a sporting event mapped in slow motion and timed to precision. Space travel became a metaphor for Politicians docking policies and jettisoning responsibility. Thrust and drag were components in a language of bodily gesture and the Saturn V rocket carrying astronauts to the moon.

The book’s main character re-staged each event to escape a tormented past. Both “The Knowledge and Beliefs of the World” and now “Landslide to be lived off… ” were also re-staging the world to prompt new ideas in a flourish of new characters. They became impossible to unpick from each character, distinguishing one person from the next. They were as inseparable as Tokyo, once home to the Luna Park amusement park destroyed by fire, and Osaka where it was later rebuilt.

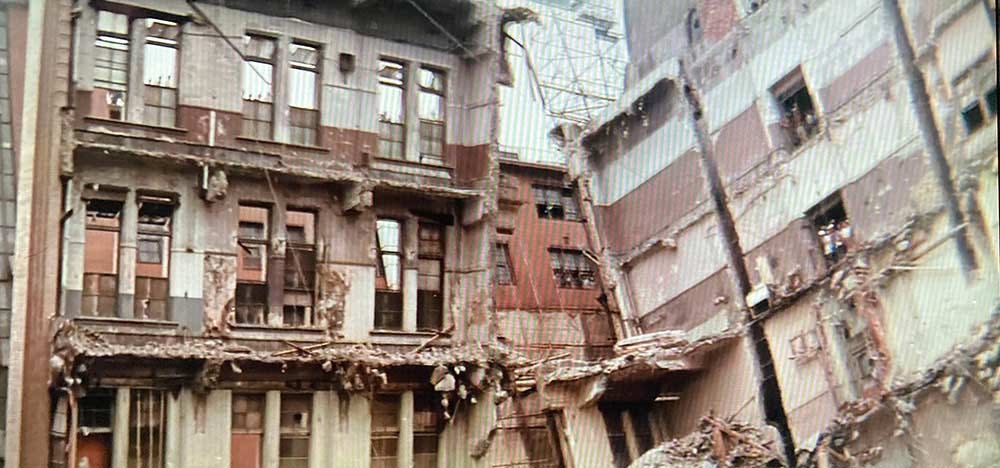

Asakusa’s Luna Park is a lost Tokyo landmark. On the afternoon on April 9th, 1911, a fire broke out under mysterious circumstances destroyed the structure. The park had been built by the wealthy businessman Ken'ichi Kawara. As owner of Yoshizawa Shōten, a family-run business he had married into, he had the means to invest in his passion for moving images and at the same time amass a small fortune. He acquired an early cinematographic device capable of recording, developing and projecting motion pictures through his own office in London and a long list of acquaintances.

Industrialist Inabata Katsutaro acquired the device from inventor Auguste Lumière through a secession of middlemen, traders and military consuls Braccialini was one, an Italian military cartographer based in Japan. Alfonso Gasco was another, being the Italian consul general in Kobe. 3

Armed with the right equipment Yoshizawa Shōten built the Denkikan, Japan’s first permanent moving picture house in Asakusa in 1903 followed by the first movie studio in Meguro, an odd glass-like structure built in 1909 which also seemed to mirror Thomas Edison’s own Bronx studio. 4 The company even published a trade magazine Katsudō shashinkai which it sent to its wealthy patrons.

Having captured the public’s imagination with their fledgling picture house and motion pictures the company opened Asakusa Luna Park in 1910 to capitalise on the success of its Coney Island namesake. Yet its success also brought envy and suspicion.

Luna Park had been open for less than a year when it was suddenly destroyed by fire. The park was so popular it attracted every sort of opportunist; shoplifters, muggers, pickpockets, prostitutes and the homeless, who authorities either turned a blind eye to or in some cases supported. 5

Either way, the fire crippled Yoshizawa Shōten. Fires had already destroyed its other two theaters in Osaka and were just as questionable. This all combined with mounting pressure from competing studios overseas eventually convinced Kawara he should sell the family business to a rival studio. But a merger seemed inevitable.

Competition also concerned Yoshizawa Shōten’s new owners who later added the studio to a consortium that gave birth to Nikkatsu, Japan’s oldest film studio. Kawara was now free of the family firm and returned to his first true passion. In July 1912, he reopened Luna Park a little more than a year later in Osaka until it finally closed in 1923.

The exhibition title “Landslide to be lived off and/or tongues to be deadpan,” MISAKO & ROSEN, 2021, featuring C Brushammer, John Grover, Luciana Janaqui, Ian Rosen, Osana Pasaiko, Hubert Van Es and Linda Warmoes, was a pun on two titles. “Language to be looked at and/or things to be read,” Dwan Gallery, 1967, 6 had been a gargantuan group show in New York featuring a bevy of artists; Carl Andre, Shusaku Arakawa, Dan Flavin, Dan Graham, Jasper Johns, On Kawara, Edward Kienholz, Sol LeWitt, Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Morris, Claes Oldenburg, and Robert Smithson amongst others. Smithson, it turned out, had written the press release and signed it with his own pseudonym, Eton Corrasable.

The second was the tongue-in-cheek artist magazine Landslide (1969-1970) published anonymously in Los Angeles by William Leavitt and Bas Jan Ader and sent to a small group of people. Mimeographed and hand-stapled, contributions came fictive artists and featured faux interviews. One interview was with John Grover, a carpenter turned minimalist sculptor, read as a parody of Dan Graham’s Homes for America (1966-1967) and mass-produced suburban architecture. Yet the contribution was just as closer if not closer to the work of Andre, not relying on weight and gravity alone to keep material in place. This was also how the installation by Grover was restaged around MISAKO & ROSEN's gallery space. Equal lengths of redwood timber rested on each other at right angles to form L-shapes, separating other works like commas in a sentence.

One of these was a video work made as “actions for two cameras” by artist Hubert Van Es, the name given to curator Florent Bex. Experiments for Autocommunication (1975) sat on the floor between two of Grover’s redwood L’s. Van Es (Bex) had used early video equipment to form ‘actions’ to communicate with himself and his own image but found the task impossible. The process was like looking in a mirror; “we never know how to look ourselves straight in the eye,” he later said. 7

Staring at these images was like staring in the face of chaos. Leavitt had claimed the magazine referred to “the southern California hillsides and their problems,” conveying a sense of entropic collapse. 8 The collapse was just as comic as was calamitous. The “expandable sculpture” of Issue 3 sent several packing peanuts in an envelope, and by issue 6 this had expanded to a McDonalds hamburger mailed out in a cardboard box.

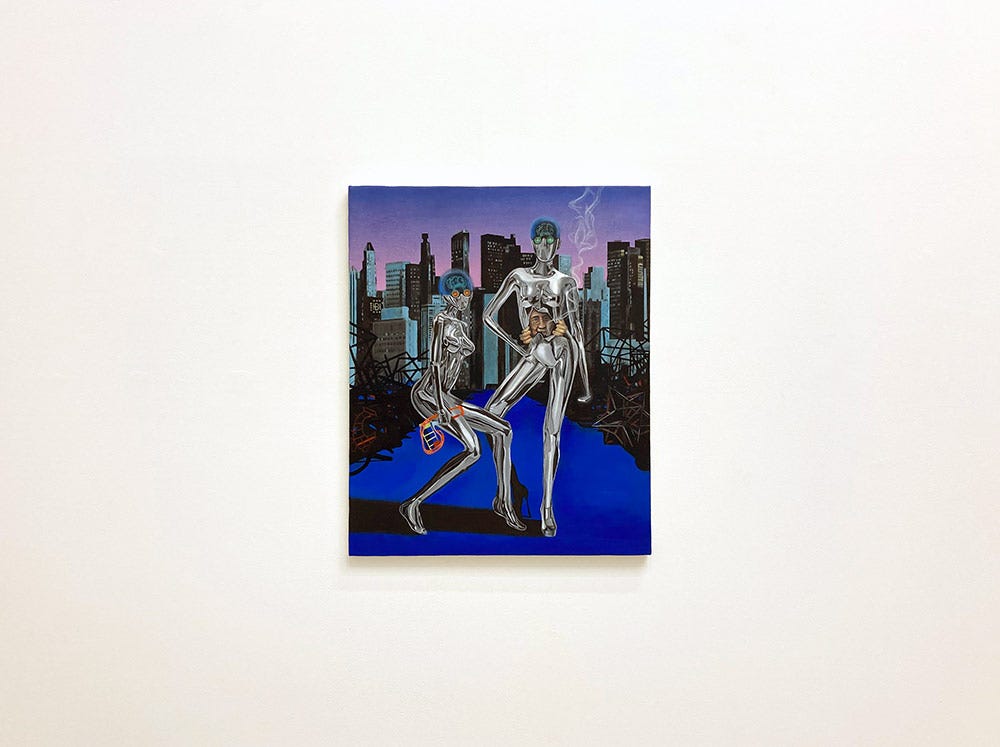

The works in “Landslide to be lived off…” were no less provocative and just as difficult to express or easily name but were anything but soulless. Brushammer’s Do Androids Dream of Frank Stella? #5 (2018) featuring Stella smoking through a Hajime Sorayama-like figure, pointed at a ghost in the machine and differences between ideas of subject and object, mind and matter.

The artworks seemed ordinary and expressionless, appeared unreadable but awe-inspiring. They mirrored how absurd the world and present moment were, prone to moments of extraordinary beauty and extreme contradiction.

For example, Takayanagi’s floor objects from “The Knowledge and Beliefs of the World” 2018, were specific things and the written statements hung from the wall were specific in their mangle of words. Thinking of them all as leaping off the screen and tele-visual made sense. As did Luna Park and EXPO’70, specific moments in time now pictured diffuse and scattered. Those pictures remained incomplete. Thoughts in these times of crisis turned from who people were to who they might be, not wrestling with a dead end but reveling in possibility.

Hunched to one side, I limped home ducking behind a citrus tree to escape the brutal heat and catch my breath. The summer seemed vague and incomplete with all its medical uncertainty. As biographies were rewritten and hillsides shored up in the heavy rain, the body seemed more conscious of what was happening, somatic in response when words were not enough.

More soon,

S

Past issues:

1. Burn it Down, Build it Up

2. Positive entropy

3. Nerves and New Skin

4. Wish you were here

5. Zone Tripper

山辺冷|Lei Yamabe

http://yukiokumura.com/writing/yamabe_edit_Japa.pdf

http://ubu.com/film/gutai_comp.html

Accessed: Monday, December 17, 2018

https://mailman.yale.edu/pipermail/kinejapan/2005-June/040984.html

Accessed: Wednesday, May 5, 2021

http://eiga9.altervista.org/chronology.html

Accessed: Wednesday, May 5, 2021

http://www.videoarchiv-ludwigforum.de/interviews/interview-with-florent-bex-a-k-a-hubert-van-es-by-lou-jonas-march-and-december-2014/

Accessed: Wednesday, September 1, 2021

Gwen Allen, Artists' Magazines: An Alternative Space for Art, MIT Press, 2011:272